Cape York Peninsula

- This article is about the peninsula located in the Australian state of Queensland; it should not be confused with either Yorke Peninsula in South Australia, or Cape York, Greenland.

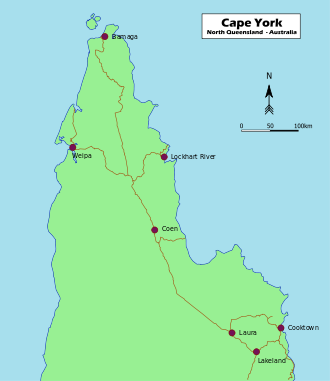

Cape York Peninsula is a large remote peninsula located in Far North Queensland at the tip of the state of Queensland, Australia, the largest unspoilt wilderness in eastern Australia and one of the last remaining wilderness areas on Earth [1]. Although the land is mostly flat and about half of the area is used for grazing cattle, and wildlife is threatened by introduced species and weeds, the relatively undisturbed eucalyptus wooded savannahs, tropical rainforests and other types of habitat are now recognized for their global environmental significance.[2]

Contents |

Geography and geology

The Cape York Peninsula region encompasses an area of approximately 137,000 km² north of 16°S latitude.[3] From the tip of the peninsula, it is about 160 kilometres (99 mi) to New Guinea across the island-studded Torres Strait.

The west coast borders the Gulf of Carpentaria and the east coast borders the Coral Sea. The peninsula is bordered on three sides (north, east and west) by water. There is no clear demarcation to the south (although the official boundary in the Cape York Peninsula Heritage Act 2007 of Queensland runs along approximately 16°S latitude[4]). The entire region covers an area of approximately 137,000 km².[3]

At the peninsula’s widest point, it is 430 km from the Bloomfield River, in the southeast, across to the west coast (just south of the Aboriginal community of Kowanyama). It is some 660 km from the southern border of Cook Shire, to the tip of Cape York. The largest islands in the strait include Prince of Wales Island, Horn Island, Moa, and Badu Island.

At the tip of the peninsula lies Cape York, the northernmost point on the Australian continent. It was named by Lieutenant James Cook on 21 August 1770 in honour of Prince Edward Augustus, Duke of York and Albany, who was a brother of King George III of the United Kingdom, and died from illness in 1767 when he was only 20 years old:

- "The point of the Main, which forms one side of the Passage before mentioned, and which is the Northern Promontory of this Country, I have named York Cape, in honour of his late Royal Highness, the Duke of York."[5]

The tropical landscapes are among the most stable in the world.[2] Long undisturbed by tectonic activity, the peninsula is an extremely eroded, almost level low plain dominated by mighty meandering rivers and vast floodplains, with some very low hills rising to some 800m elevation in the McIlwraith Range on the eastern side around Coen.

The backbone of Cape York Peninsula is the Peninsula Ridge, part of Australia’s Great Dividing Range. This mountain range is made up of ancient (1,500 million year-old) Precambrian and Palaeozoic rocks.[2][3] To the East and West of the Peninsula Ridge lie the Carpentaria and Laura Basins, themselves made up of ancient Mesozoic sediments.[3]. There are several outstanding landforms on the peninsula: the large expanses of undisturbed dunefields at the eastern coast around Shelburne Bay and Cape Bedford-Cape Flattery; the huge piles of black granite boulders at Black Mountain National Park and Cape Melville; and the limestone karsts around Palmerston in the Cape’s far south.[2]

The soils are remarkably infertile even compared to other areas of Australia, being almost entirely laterised and in most cases so old and weathered that very little development is apparent today (classified in USDA soil taxonomy as Orthents). It is because of this extraordinary soil poverty that the region is so thinly settled: the soils are so unworkable and unresponsive to fertilisation that attempts to grow commercial crops have usually failed.

The climate on Cape York Peninsula is tropical and monsoonal, with a heavy monsoon season from November to April, during which time the forest becomes almost inhabitable, and a dry season from May to October. The temperature is warm to hot, with a cooler climate in higher areas. The mean annual temperatures range from 18 °C at higher elevations to 27 °C on the lowlands in the drier south-west. Temperatures over 40 °C and below 5 °C are rare.

Annual rainfall is high, ranging from over 2000 mm. in the Iron Range and north of Weipa to about 700 mm. at the southern border. Almost all this rain falls between November and April, and only on the eastern slopes of the Iron Range is the median rainfall between June and September above 5mm (0.2 inches). Between January and March, however, the median monthly rainfall ranges from about 170mm (6.5 inches) in the south to over 500mm (20 inches) in the north and on the Iron Range.

| Climate data for Cape York | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average high °C (°F) | 29.8 (85.6) |

29.6 (85.3) |

29.6 (85.3) |

29.5 (85.1) |

28.8 (83.8) |

28.1 (82.6) |

27.6 (81.7) |

27.8 (82) |

28.5 (83.3) |

29.9 (85.8) |

30.9 (87.6) |

30.8 (87.4) |

29.2 (84.6) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 24.0 (75.2) |

23.9 (75) |

23.8 (74.8) |

23.7 (74.7) |

23.0 (73.4) |

22.3 (72.1) |

21.5 (70.7) |

21.6 (70.9) |

22.2 (72) |

22.9 (73.2) |

23.8 (74.8) |

24.2 (75.6) |

23.1 (73.6) |

| Precipitation mm (inches) | 370.6 (14.591) |

352.1 (13.862) |

370.9 (14.602) |

255.5 (10.059) |

69.1 (2.72) |

26.1 (1.028) |

19.7 (0.776) |

9.5 (0.374) |

6.4 (0.252) |

14.9 (0.587) |

56.7 (2.232) |

194.6 (7.661) |

1,744.7 (68.689) |

| Source: [6] | |||||||||||||

Rivers

The Peninsula Ridge forms the drainage divide between the Gulf of Carpentaria and the Coral Sea. To the west, a series of large, winding river systems including the Mitchell, Coleman, Holroyd, Archer, Watson, Wenlock, Ducie and Jardine catchments empty their waters into the Gulf of Carpentaria. During the Dry season, those rivers are reduced to a series of waterholes and sandy beds. Yet, with the arrival of torrential rains in the Wet season, they swell to mighty waterways, spreading across extensive floodplains and coastal wetlands and giving life to a vast array of freshwater and wetland species.[3]

On the Eastern slopes, the shorter, faster-flowing Jacky Jacky Creek, Olive, Pascoe, Lockhart, Stewart, Jeannie and Endeavour Rivers flow towards the Coral Sea, providing important freshwater and nutrients to the healthiest section of the Great Barrier Reef. On their way, those wild, undisturbed rivers are lined with dense rainforests, sand dunes or mangroves.[3]

The floodplains of the Laura Basin, which are protected in the Lakefield and Jack River National Parks, are crossed by the Morehead, Hann, North Kennedy, Laura, Jack and Normanby Rivers.

The Peninsula’s river catchments are noted for their exceptional hydrological integrity. With little disturbance on both water flows and vegetation cover throughout entire catchments, Cape York Peninsula has been identified as one of the few places where tropical water cycles remain essentially intact.[2] Cape York Peninsula contributes as much as a quarter of Australia's surface runoff. Indeed, with only about 2.7 percent of Australia's land area it produces more run-off than all of Australia south of the Tropic of Capricorn. Tapping those heavy tropical rainfalls, the peninsula’s rivers are also of particular importance for replenishing central Australia’s Great Artesian Basin.[2] The Queensland Government is currently poised to protect 13 of Cape York Peninsula’s wild rivers under the Wild Rivers Act 2005.[7]

Geological history

Around 40 million years ago, the Indo-Australian tectonic plate began to split apart from the ancient supercontinent Gondwana. As it collided with the Pacific Plate on its northward journey, the high mountain ranges of central New Guinea emerged around 5 million years ago.[3] In the lee of this collision zone, the ancient rock formations of what is now Cape York Peninsula remained largely undisturbed.

Throughout the Pleistocene epoch Australia and New Guinea have been alternately land-linked and separated by water on a number of occasions. During periods of glaciation and resulting low sea levels, Cape York Peninsula provided a low-lying land link.[2] Another link existed between Arnhem Land and New Guinea, at times enclosing an enormous freshwater lake (Lake Carpentaria) in the centre of what is now the Gulf of Carpentaria.[8] In this way, Australia and New Guinea remained connected until the shallow Torres Strait was last flooded around 8,000 years ago.[1]

Ecology

Flora

Cape York Peninsula supports a complex mosaic of intact tropical rainforests, tropical and subtropical grasslands, savannahs, and shrublands|tropical savannahs, heath lands, wetlands, wild rivers and mangrove swamps.[2] These various habitats are home to about 3300 species of flowering plants[9] and almost the entire area of Cape York Peninsula (99.6%) still retains its native vegetation and is little fragmented.[9] Cape York Peninsula also contains one of the highest rates of endemism in Australia, with more than 260 endemic plant species found so far[2][10][11]. Therefore, parts of the Peninsula have been noted for their exceptionally high wilderness quality.[10] The flora of the peninsula includes original Gondwanan species, plants that have emerged since the breakup of Gondwana and species from Indo-Malaya and from across the Torres Strait in New Guinea with the most variety being found in the rainforest areas. Most of the Cape York Peninsula is drier than nearby New Guinea which limits the rainforest plants of that island from migrating across to Australia.[12]

The majority of Cape York Peninsula is covered in tropical and subtropical grasslands, savannahs, and shrublands|tropical savannah woodland consisting typically of a tall dense grass layer and varying densities of trees, dominantly eucalypts of which the most common is Darwin stringybark.[8] Although abundant and fully functioning on the peninsula, tropical savannahs are now rare and highly degraded in other parts of the world.[2]

Tropical rainforests cover an area of 748,000 ha, or 5.6 percent of the total land area of Cape York Peninsula.[13] Rainforests depend on some level of rainfall throughout the long Dry season, climatic conditions that are mostly found on the eastern slopes of the Cape’s coastal ranges. Being almost exclusively untouched, old-growth forests and supporting a disproportionately high biodiversity including flora of Gondwanan and New Guinean origin, the rainforests are of high conservation significance.[10] The largest contiguous rainforest area on the Cape occurs in the McIllwraith Range-Iron Range area.[8] The Gondwanan flora of this area includes Araucariaceae and Podocarpaceae conifers and Arthrochilus, Corybas, and Calochilus orchids. In all this rainforest contains at least 1000 different plants, including 100 rare or threatened species, and 16% of Australia's orchid species.

On poor, dry soils tropical heathlands can be found. North-east Cape York Peninsula supports Australia’s largest areas of this highly diverse ecosystem.[8]

The extensive wetlands on Cape York Peninsula are “among the largest, richest and most diverse in Australia”.[10] 19 wetlands of national significance have been identified, mostly on the large floodplains and in coastal areas. Important wetlands include the Jardine Complex, Lakefield systems and the estuaries of the great rivers of the western plains.[10] Many of these wetland come into existence only during the Wet season and support rare or uncommon plant communities.[13]

The Peninsula’s coastal areas and river estuaries are lined with mangrove forests of kwila and other trees. Australia’s largest mangrove forest can be found at Newcastle Bay.

Fauna

The Cape harbours an extraordinary biodiversity, with more than 700 vertebrate land animal species of which 40 are endemic. As a result from its geological history, “the flora and fauna of Cape York Peninsula are a complex mixture of Gondwanan relics, Australian isolationists and Asian or New Guinean invaders” (p. 41).[3] Birds of the peninsula include Buff-breasted Buttonquail (Turnix olivii), Golden-shouldered Parrot (Psephotus chrysopterygius), Lovely Fairywren (Malurus amabilis), White-streaked Honeyeater (Trichodere cockerelli), and Yellow-spotted Honeyeater (Meliphaga notata) while some such as Pied Oystercatcher are found in other parts of Australia but have important populations on the peninsula. The Cape is also home to the Eastern brown snake, one of the world's most venomous snakes. Mammals include the endangered rodent Bramble Cay Melomys found only on Bramble Cay in the Torres Strait.

The rainforests of the Iron Range support species that are also found in New Guinea, including the Eclectus Parrot and Southern Common Cuscus. Other rainforest fauna includes 200 species of butterfly including 11 endemic butterflies one of which is the huge Green Birdwing, the Green Tree Python and the Northern Quoll a forest marsupial that is now severely depleted from eating the introduced poisonous cane toads.

The riverbanks of the lowlands are home to specific wildlife of their own while the rivers including the Jardine, Jackson, Olive, Holroyd and the Wenlock are rich in fish. The wetlands and coastal mangroves are noted for their importance as a fish nursery and crocodile habitat, providing important drought refuge [8][10] and finally the Great Barrier Reef lies off the east coast and is an important marine habitat.

Threats and preservation

Cattle ranch leases occupy about 57% of the total area, mostly located in central and eastern Cape York Peninsula. Indigenous land comprises about 20%, with the entire West coast being held under Native title. The remainder is mostly declared as [National Park] and managed by the Queensland Parks and Wildlife Service. Land uses include broad acre pastoralism, bauxite and silica sand mining, nature reserves, tourism and fishing. There are extensive deposits of bauxite along the west or Gulf of Carpentaria coast. Weipa is the centre for mining.[14][15] Much has been damaged by overgrazing, mining, poorly controlled fires and feral pigs, cane toads, weeds, and other introduced species[16][17] but Cape York Peninsula remains fairly unspoilt with intact and healthy river systems and no recorded plant or animal extinction since European settlement.

The "Cape York Peninsula Land Use Strategy" study was commissioned by the Australian government in 1990 to create plans to protect the wilderness and a nomination for World Natural Heritage is currently being considered by the Queensland and Australian Federal governments.[18] Major national parks include the Jardine River National Park in the far north, Mungkan Kandju National Park near Aurukun, and Lakefield National Park in the southeast of the bioregion.

People and culture

The first known contact between Europeans and Aborigines occurred on the west coast of the peninsula in 1606 but it was not settled by Europeans until the 19th century when fishing communities, then ranches and later mining towns were established. European settlement led to the displacement of Aboriginal communities and the arrival of Torres Strait Islanders on the mainland. Today the peninsula has a population of only about 18,000, of which a large percentage (~60 %) are Aborigines and Torres Strait Islanders.[8][19]

The administrative and commercial centre for much of Cape York Peninsula is Cooktown, located in its far south-eastern corner while the peninsula’s largest settlement is the mining town Weipa on the Gulf of Carpentaria. The remainder is extremey sparsely populated with about half the population living in very small settlements and cattle ranches. Along the Peninsula Developmental Road, there are small service centres at Lakeland, Laura and Coen. At the tip of Cape York, there is a sizeable service centre on nearby Thursday Island. Aboriginal communities are at Hopevale, Pormpuraaw, Kowanyama, Aurukun, Lockhart River, Napranum, Mapoon, Injinoo, New Mapoon and Umagico. Torres Strait Islander communities on the mainland are at Bamaga and Seisia.[2][19] A completely sealed inland road links Cairns and the Atherton Tableland to Lakeland Downs and Cooktown. The road north of Lakeland Downs to the tip of the Peninsula is sometimes cut after heavy rains during the wet season (roughly December to May).

The Peninsula is a popular tourist destination in the Dry Season for camping, hiking, birdwatching and fishing enthusiasts. Many people make the adventurous, but rewarding, drive to the tip of Cape York, the northernmost point of mainland Australia.

Some of the world's most extensive and ancient Aboriginal rock painting galleries surround the town of Laura, some of which are available for public viewing. There is also a new Interpretive Centre from which information on the rock art and local culture is available and tours can be arranged.

Solar eclipse

As weather permits, the next total eclipse of the sun should be visible from Cape York, Australia, as well as some northern islands of New Zealand. This eclipse will occur on November 13, 2012. Visitors may wish to invest in snake boots. This eclipse is listed in the List of solar eclipses in the 21st century article.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Mittermeier, R.E. et al. (2002). Wilderness: Earth’s last wild places. Mexico City: Agrupación Sierra Madre, S.C.

- ↑ 2.00 2.01 2.02 2.03 2.04 2.05 2.06 2.07 2.08 2.09 2.10 Mackey, B. G., Nix, H., & Hitchcock, P. (2001). The natural heritage significance of Cape York Peninsula. Retrieved January 15, 2008, from http://www.epa.qld.gov.au/register/p00582aj.pdf.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 3.6 3.7 Frith, D.W., Frith, C.B. (1995). Cape York Peninsula: A Natural History. Chatswood: Reed Books Australia. Reprinted with amendments in 2006. ISBN 0-7301-0469-9.

- ↑ Office of the Queensland Parliamentary Counsel. (2007). Cape York Peninsula Heritage Act 2007. Retrieved March 23, 2008, from http://www.legislation.qld.gov.au/LEGISLTN/CURRENT/C/CapeYorkPHA07.pdf

- ↑ From Cook's Journal

- ↑ "BOM". http://www.bom.gov.au/climate/averages/tables/cw_027004.shtml.

- ↑ Office of the Queensland Parliamentary Counsel. (2005). Wild Rivers Act 2005. Retrieved March 23, 2008, from http://www.legislation.qld.gov.au/LEGISLTN/ACTS/2005/05AC042.pdf.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 8.4 8.5 Woinarski, J., Mackey, B., Nix, H., Traill, B. (2007). The nature of northern Australia: Natural values, ecological processes and future prospects. Canberra: ANU E press.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Neldner, V.J., Clarkson, J.R. (1994). Vegetation Survey of Cape York Peninsula. Cape York Peninsula Land Use Study (CYPLUS). Office of the Co-ordinator General and Department of Environment and Heritage, Government of Queensland: Brisbane.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 10.4 10.5 Abrahams, H., Mulvaney, M., Glasco, D., Bugg, A. (1995). Areas of Conservation Significance on Cape York Peninsula. Cape York Peninsula Land Use Strategy. Office of the Co-ordinator General of Queensland,Australian Heritage Commission. Accessed January 15, 2008, http://www.environment.gov.au/erin/cyplus/lup/index.html.

- ↑ Wildlife of Tropical North Queensland. (2000). Queensland Museum. ISBN 0-7242-9349-3.

- ↑ http://www.worldwildlife.org/wildworld/profiles/terrestrial/aa/aa0703_full.html

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Cofinas, M., Creighton, C. (2001). Australian Native Vegetation Assessment. National Land and Water Resources Audit. Accessed April 20, 2008, http://www.anra.gov.au/topics/vegetation/pubs/native_vegetation/nat_veg_contents.html.

- ↑ (Sattler & Williams, 1999)

- ↑ Australian Government. Australian Natural Resource Atlas. Accessed April 20, 2008, http://www.anra.gov.au/topics/rangelands/overview/qld/ibra-cyp.html.

- ↑ Wynter, Jo and Hill, John. 1991. Cape York Peninsula: Pathways to Community Economic Development. The Final Report of The Community Economic Development Projects Cook Shire. Cook Shire Council.

- ↑ [1]

- ↑ Valentine, Peter S. (2006). Compiling a case for World Heritage on Cape York Peninsula. Retrieved February 7, 2008, from http://www.epa.qld.gov.au/publications/p02227aa.pdf/Compiling_a_case_for_World_Heritage_on_Cape_York_Peninsula_Final_report_for_QPWS_/_compiled_by_Peter_S_Valentine_James_Cook_University.pdf.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Cape York Peninsula Development Association. Homepage. Accessed April 23, 2008, http://www.cypda.com.au/front_page.

Further references

- Hough, Richard. 1994. Captain James Cook: a biography. Hodder and Stroughton, London. ISBN 0-340-58598-6.

- Pike, Glenville. 1979. Queen of the North: A Pictorial History of Cooktown and Cape York Peninsula. G. Pike. ISBN 0-9598960-5-8.

- Moon, Ron & Viv. 2003. Cape York: An Adventurer's Guide. 9th edition. Moon Adventure Publications, Pearcedale, Victoria. ISBN 0-9578766-4-5

- Moore, David R. 1979. Islanders and Aborigines at Cape York: An ethnographic reconstruction based on the 1848-1850 'Rattlesnake' Journals of O. W. Brierly and information he obtained from Barbara Thompson. Australian Institute of Aboriginal Studies. Canberra. ISBN 0-85575-076-6 (hbk); 0-85575-082-0 (pbk). USA edition ISBN 0-391-00946-X (hbk); 0-391-00948-6 (pbk).

- Pohlner, Peter. 1986. gangaurru. Hopevale Mission Board, Milton, Queensland. ISBN 1-86252-311-8

- Trezise, P.J. 1969. Quinkan Country: Adventures in Search of Aboriginal Cave Paintings in Cape York. A.H. & A.W. Reed, Sydney.

- Trezise, Percy. 1973. Last Days of a Wilderness. William Collins (Aust) Ltd., Brisbane. ISBN 0-00-211434-8.

- Trezise, P.J. 1993. Dream Road: A Journey of Discovery. Allen & Unwin, St. Leonards, Sydney.

- Haviland, John B. with Hart, Roger. 1998. Old Man Fog and the Last Aborigines of Barrow Point. Crawford House Publishing, Bathurst.

- Premier's Department (prepared by Connell Wagner). 1989. Cape York Peninsula Resource Analysis. Cairns. (1989). ISBN 0-7242-7008-6.

- Roth, W.E. 1897. The Queensland Aborigines. 3 Vols. Reprint: Facsimilie Edition, Hesperian Press, Victoria Park, W.A., 1984. ISBN 0-85905-054-8

- Ryan, Michelle and Burwell, Colin, eds. 2000. Wildlife of Tropical North Queensland: Cooktown to Mackay. Queensland Museum, Brisbane. ISBN 0-85905-045-9 (set of 3 vols).

- Scarth-Johnson, Vera. 2000. National Treasures: Flowering plants of Cooktown and Northern Australia. Vera Scarth-Johnson Gallery Association, Cooktown. ISBN 0-646-39726-5 (pbk); ISBN 0-646-39725-7 Limited Edition - Leather Bound.

- Sutton, Peter (ed). Languages of Cape York: Papers presented to a Symposium organised by the Australian Institute of Aboriginal Studies. Australian Institute of Aboriginal Studies, Canberra. (1976). ISBN 0-85575-046-4

- Wallace, Lennie. 2000. Nomads of the 19th Century Queensland Goldfields. Central Queensland University Press, Rockhampton. ISBN 1-875998-89-6

- Wallace, Lennie. 2003. Cape York Peninsula: A History of Unlauded Heroes 1845-2003. Central Queensland University Press, Rockhampton. ISBN 1-876780-43-6

- Wynter, Jo and Hill, John. 1991. Cape York Peninsula: Pathways to Community Economic Development. The Final Report of The Community Economic Development Projects Cook Shire. Cook Shire Council.

|

|||||||||||||||||